On August 18, 2025, gravitational wave observatories captured a signal that might represent the initial discovery of a "superkilonova," a theoretical cosmic phenomenon.

Kilonovae occur when two neutron stars—dense remnants of massive stars—collide, generating conditions extreme enough to produce heavy elements like gold and silver. These events release both gravitational waves and electromagnetic radiation.

Superkilonovae differ by originating from a supernova explosion that creates two neutron stars, which then spiral together and merge. This process combines features of both supernovae and kilonovae.

Previously, only one confirmed kilonova detection existed: GW170817 in 2017, observed by LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors along with traditional telescopes.

The recent signal, designated AT2025ulz, initially appeared similar to the 2017 kilonova. "At first, for about three days, the eruption looked just like the first kilonova in 2017," stated Mansi Kasliwal, astronomy professor at Caltech and lead researcher. "Everybody was intensely trying to observe and analyze it, but then it started to look more like a supernova, and some astronomers lost interest. Not us."

Unusual Characteristics

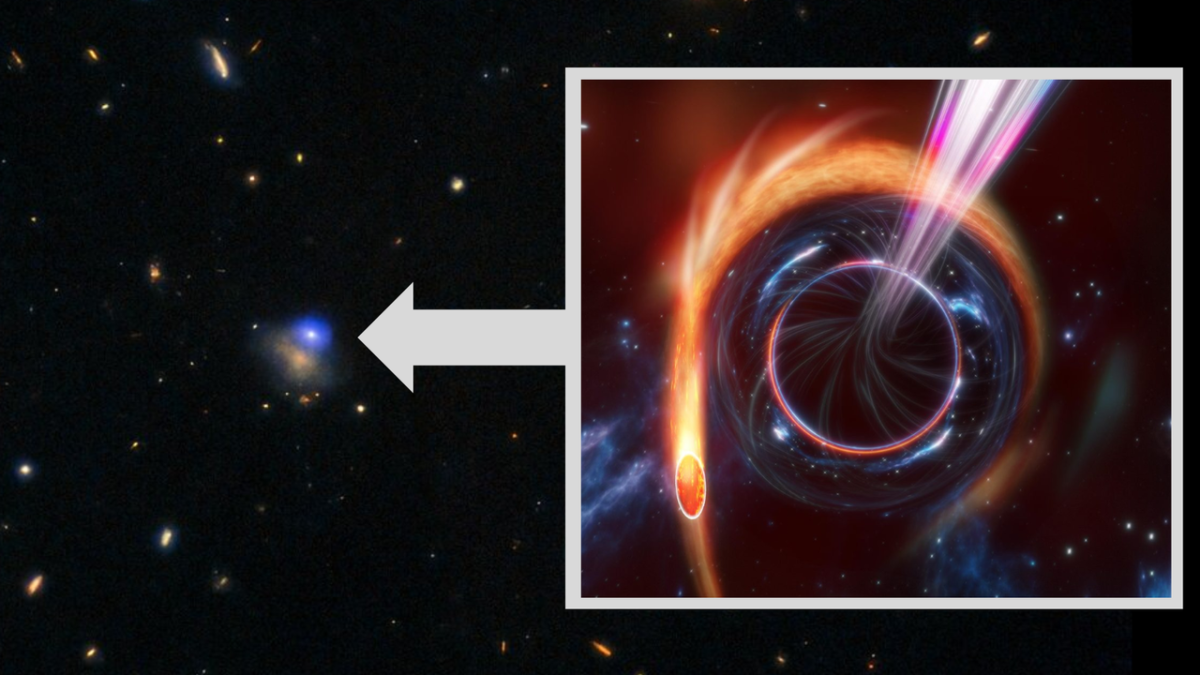

Following the gravitational wave detection, telescopes including the Zwicky Transient Facility in California identified a rapidly fading red object approximately 1.3 billion light-years away, matching the wave source location.

Initially, AT2025ulz displayed the red glow characteristic of kilonovae, caused by heavy elements blocking blue light while allowing red wavelengths through—identical to GW170817's pattern.

However, days later, the event brightened and turned blue with hydrogen emissions, traits typical of supernovae. This created a puzzle: while supernovae produce gravitational waves, one at this distance shouldn't generate waves detectable by LIGO.

Further analysis revealed the gravitational wave signal indicated one merging neutron star had mass below solar levels. Typical neutron stars range from 1.2 to two solar masses, suggesting unusually small neutron stars might have merged.

Formation Theories

Scientists propose two mechanisms for creating sub-solar-mass neutron stars. First, a rapidly spinning star undergoing supernova might fission into two smaller neutron stars. Alternatively, a supernova could produce a neutron star surrounded by material that forms a companion neutron star, similar to planetary formation around young stars.

In both scenarios, these neutron stars emit gravitational waves as they orbit, losing angular momentum and eventually merging to produce heavy elements—explaining the observed red glow.

"The only way theorists have come up with to birth sub-solar neutron stars is during the collapse of a very rapidly spinning star," explained team member Brian Metzger of Columbia University. "If these 'forbidden' stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, it is possible that such an event would be accompanied by a supernova rather than be seen as a bare kilonova."

The expanding supernova debris eventually obscured the kilonova view, complicating observations.

Future Investigations

Current data remains insufficient for definitive confirmation. "Future kilonovae events may not look like GW170817 and may be mistaken for supernovae," Kasliwal noted. "We can look for new possibilities in data like this from ZTF as well as the Vera Rubin Observatory, and upcoming projects such as NASA's Nancy Roman Space Telescope, NASA's UVEX, Caltech's Deep Synoptic Array-2000, and Caltech's Cryoscope in the Antarctic. We do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova, but the event is nevertheless eye-opening."

This research contributes to understanding extreme cosmic events and heavy element formation in the universe.