Antarctica's massive ice sheet, centered over the South Pole, gives the appearance of a single frozen continent. However, the West Antarctic portion is particularly dynamic, shaped like a hitchhiker's thumb and currently in motion. As Earth's oceans and atmosphere warm, this ice sheet is melting, flowing outward, and shrinking at remarkable rates.

Focus Beyond Human Impacts

While discussions often center on how melting ice affects human populations through sea-level rise, a crucial question remains: What transformations will Antarctica itself undergo as its ice disappears?

Scientists examining seafloor sediments millions of years old have discovered evidence that West Antarctica's past melting triggered intense geological upheaval on land. This historical record provides a preview of future changes.

Uncovering Ancient Climates

Antarctica has been ice-covered for approximately 30 million years. During the Pliocene Epoch, from 5.3 to 2.6 million years ago, the West Antarctic ice sheet experienced a major retreat. Instead of a continuous sheet, only isolated ice caps and mountain glaciers remained.

Around 5 million years ago, warming conditions began reducing West Antarctic ice. By about 3 million years ago, a global warm phase similar to today's climate was underway.

Glaciers, which form on land and flow seaward, act like conveyor belts, scraping bedrock and transporting debris. This process accelerates in warmer climates, as does iceberg calving. These icebergs can carry continental rock far out to sea before melting and depositing their load on the seabed.

Expedition to the Amundsen Sea

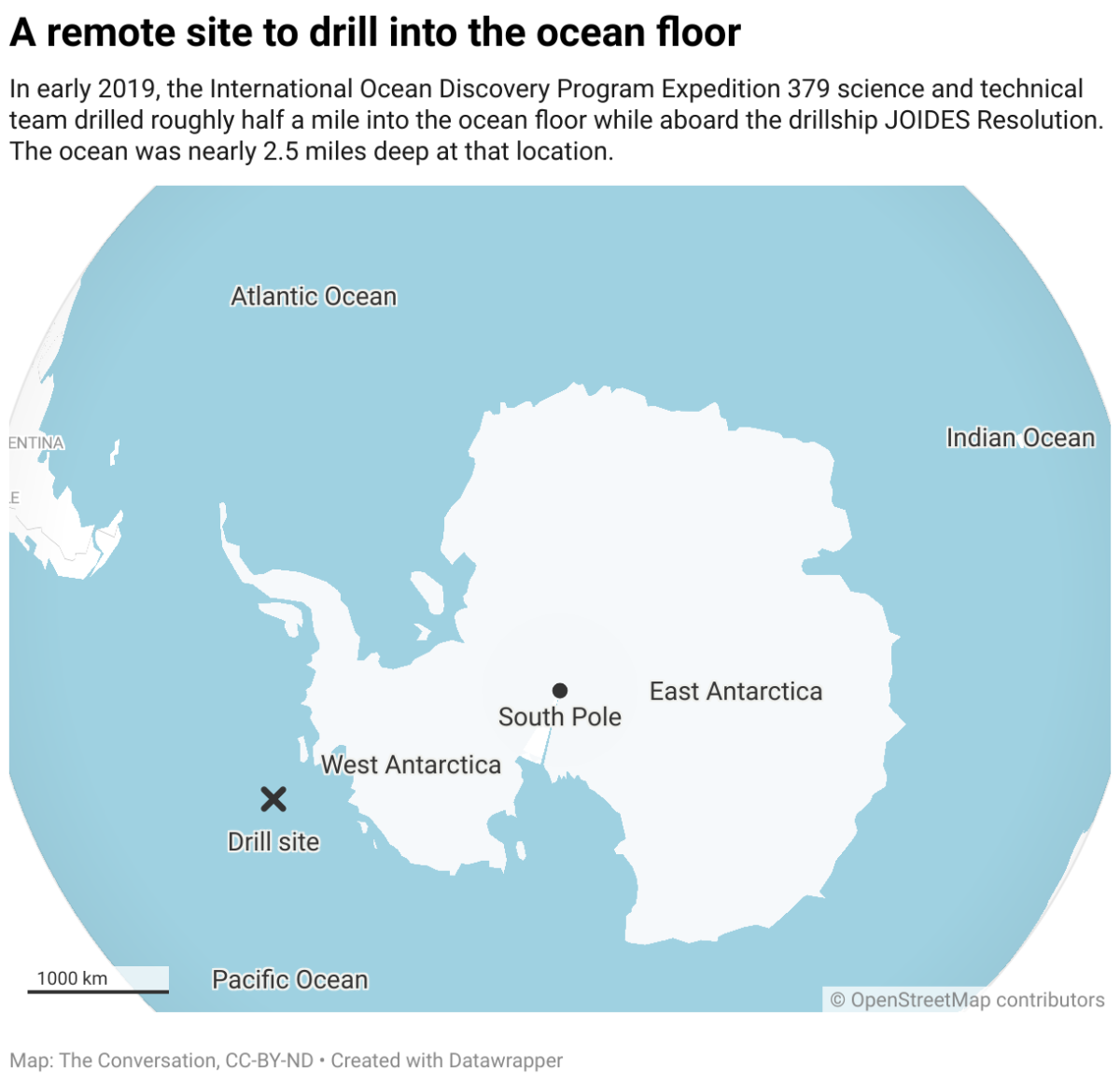

In early 2019, researchers participated in International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 379 to the Amundsen Sea. The mission aimed to recover seabed material to understand West Antarctica's ancient melting period.

Aboard the JOIDES Resolution drillship, a drill descended nearly 13,000 feet to the seafloor and penetrated an additional 2,605 feet into the ocean bed, offshore from the most vulnerable part of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

The operation retrieved sediment cores containing layers deposited from 6 million years ago to the present. The research focused on Pliocene-era sediments, when Antarctica was not fully ice-covered.

A Revealing Pebble

During the expedition, researcher Christine Siddoway discovered an unusual sandstone pebble in a disturbed core section. Such fragments were rare, making its origin significant. Analysis revealed the pebble originated from mountains deep in Antarctica's interior, roughly 800 miles from the drill site.

This finding indicated that icebergs had calved from glaciers flowing off interior mountains and floated toward the Pacific. It provided evidence that a deep-water ocean passage, not today's thick ice sheet, once existed across Antarctica's interior.

Post-expedition laboratory analyses of silt, mud, rock fragments, and microfossils confirmed this. The chemical and magnetic properties of the core material outlined a detailed timeline of the ice sheet's retreats and advances over millennia.

Chemical Fingerprints and Repeated Cycles

Keiji Horikawa led analyses matching thin mud layers in the cores to continental bedrock, testing the theory of long-distance iceberg transport. Each mud layer was deposited immediately after a deglaciation episode when the ice sheet retreated, leaving a bed of iceberg-carried clay with pebbles.

By measuring elements like strontium, neodymium, and lead, he linked specific mud layers to chemical signatures in the Ellsworth Mountains, 870 miles away. Horikawa identified up to five such mud layers deposited between 4.7 and 3.3 million years ago.

This suggests the ice sheet melted, forming open ocean, then regrew to fill the interior repeatedly over spans of thousands to tens of thousands of years.

Modeling a Transformed Landscape

Ruthie Halberstadt integrated this chemical evidence and timing into computer models. These simulations showed how an archipelago of rugged, ice-capped islands emerged as ocean replaced the thick ice sheets filling Antarctica's interior basins.

The most significant changes occurred along the coast. Models indicated a rapid increase in iceberg production and a dramatic retreat of the ice sheet edge toward the Ellsworth Mountains. The Amundsen Sea became clogged with icebergs from all directions. Rocks and pebbles embedded in glaciers floated out within icebergs and dropped to the seabed as the ice melted.

Geological Consequences of Ice Loss

Global geological evidence shows that as ice melts and flows off land, the underlying land rises because the weight of the ice is removed. This shift can induce earthquakes, especially in West Antarctica, which sits above hot mantle areas that rebound quickly when ice melts.

The pressure release also boosts volcanic activity, as seen in Iceland today. Evidence in Antarctica includes a 3-million-year-old volcanic ash layer identified in the cores by Siddoway and Horikawa.

The ancient ice loss and land uplift in West Antarctica also triggered massive rock avalanches and landslides along glacial valley walls and coastal cliffs. Submarine collapses displaced vast sediment masses from the marine shelf. Without the stabilizing weight of glacier ice and ocean water, huge rock masses broke away and surged into the water, generating tsunamis that caused further coastal destruction.

This rapid onset of changes made deglaciated West Antarctica an exemplar of "catastrophic geology."

Echoes of Past Ice Ages

This rapid surge in activity mirrors events elsewhere. For instance, at the end of the last Northern Hemisphere ice age, 15,000 to 18,000 years ago, the region from Utah to British Columbia experienced floods from bursting glacial lakes, land rebound, rock avalanches, and increased volcanic activity. Similar events continue in coastal Canada and Alaska today.

Implications for a Dynamic Future

The team's analysis of rock chemistry clarifies that West Antarctica does not undergo a single, gradual shift from ice-covered to ice-free. Instead, it oscillates between vastly different states. Each past disappearance of the ice sheet led to geological chaos.

The future implication is that when the West Antarctic ice sheet collapses again, these catastrophic events will return. This cycle will repeat as the ice sheet retreats and advances, opening and closing connections between different world oceans.

This dynamic future may also prompt swift biological responses, such as algal blooms around icebergs, leading to an influx of marine species into newly opened seaways. Vast tracts of land on West Antarctic islands would become available for mossy ground cover and coastal vegetation, making Antarctica greener than its current icy white.

Data from the Amundsen Sea's past and resulting forecasts indicate that onshore changes in West Antarctica will not be slow, gradual, or imperceptible from a human perspective. Instead, what occurred historically is likely to recur: geologically rapid shifts felt locally as apocalyptic events like earthquakes, eruptions, landslides, and tsunamis—with worldwide effects.